Why Cellphones Might Be the Next Great Public Health Tool

A new study found that SMS polls can help rapidly gather health information.

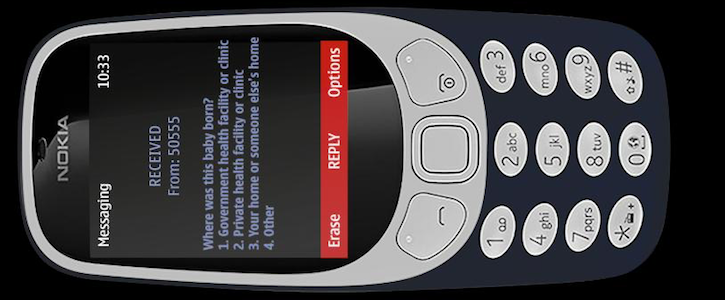

Researchers sent text messages to people in Ebola-stricken Liberia. Credit: GeoPoll

In spring 2015, Liberia was suffering a deadly Ebola outbreak. It wasn’t the first time the virus had gripped the African nation, and it was unlikely to be the last. But there was something different about this particular outbreak.

The distinction, however, was not found in the particular strain of Ebola or even its toll on Liberia’s population. Instead, it was a change in how public health researchers used technology to contact — and learn from — patients and people on the ground.

>> READ: mHealth Is Powered by Potential but Dogged by Dubious Studies

Researchers from New York University’s College of Global Public Health and Tandon School of Engineering issued a poll and received responses from 6,694 individuals — via text messages sent to their cellphones. The 10-question survey focused on how Liberians were using maternal health services during the outbreak. The effort revealed a decline in hospital-based births, which returned to typical levels once the Ebola outbreak was quashed, suggesting that people were afraid to visit the hospital, according to a new study describing the campaign.

But these findings supported a much larger implication: The study demonstrated how cellphones and text messages can be useful public health tools, especially in times of crisis.

“While text messages will not replace national surveys, they can capture changes in health behavior more nimbly,” noted lead author Rumi Chunara, Ph.D., M.S., an NYU assistant professor of computer science and engineering and global public health. “With appropriate methodological approaches, they can be a valuable tool for population health intelligence that allows us to quickly target the affected regions with public health messaging or deploy appropriate interventions.”

Typically, public health researchers and government responders survey affected populations by household or healthcare facility. This process can take months, and emergencies such as a viral outbreak can cause delays or even sink such efforts.

Chunara’s finding — that the number of in-hospital births “significantly decreased” during the Ebola outbreak — further illustrated this problem. If public health officials hoped to reach people through health institutions, they would have been out of luck.

“If you want to deploy treatment or interventions, you need to know if people are coming to hospitals or staying in their communities,” she added.

Cellphones solve that problem.

In Liberia, 81 percent of the population had a cellphone plan in 2015. To incentivize participants, researchers promised them 50 cents in phone credit, a tactic that has proved successful in other cases.

Still, the study was limited in that younger, more affluent and educated nature of cellphone users, posing an obstacle to gathering data that are representative of the population at large. But researchers used propensity score matching to balance population factors, according to the study.

Finally, they concluded that drops in the number of births occurred in both public and private hospitals.

In the future, this sort of digital campaign can be used to provide insights into flu epidemics, as individuals who come down with the illness don’t always seek medical treatment.

“As mobile phone ownership, and even smartphone use, is growing even among poorer segments of the population, and given its low cost, with appropriate methodological approaches, it can be a valuable tool for population health intelligence,” the researchers included.

And such an arrangement could even evolve to help governments and experts push forth digital health interventions.

Get the best insights in healthcare analytics directly to your inbox.

Related

4 Ways Mobile Tech Is Driving Digital Health Research

Telemedical Drones Are Increasing Access to Care in the Face of Natural Disasters