State-Level Influenza 'Nowcasting' Remains a Thorny Issue

Why a new model designed to tabulate localized influenza outbreaks faces significant hurdles.

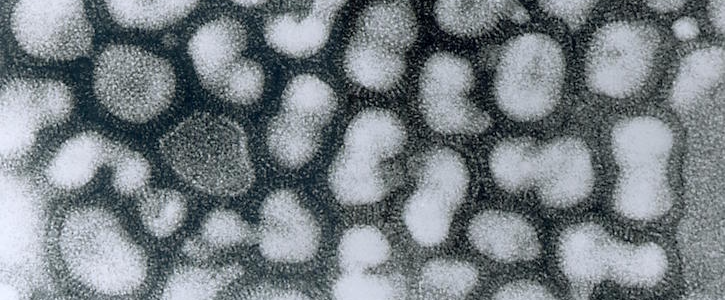

Image: CDC/ Dr. Erskine Palmer

A new study leveraging online search trends to gain a picture of current, local influenza outbreaks is showing some signs of promise, though researchers say they remain hamstrung by a lack of access to complete live data.

Monitoring and forecasting influenza and flu-like illnesses can be a critical tool for public health officials. But while forecasting models continue to become more widely available, they generally don’t have the ability to predict accurate results at the local level.

To remedy that, scientists have developed ways to use data from local health departments, along with surveys of flu symptom mentions in search queries and social media posts, to gain a picture of what’s happening in a given area.

The most prominent effort at influenza “nowcasting” was Google Flu Trends (GFT), a program first developed by Google in 2008 to surveil internet postings for signs that flu outbreaks were occurring. However, the company shelved that effort after it was shown in 2013 to have badly overestimated instances of the flu.

Picking up the baton, researchers from Columbia University recently developed their own “nowcasting” model, which used flu-like illness data at the state level, along with web-based search activity from Google Extended Trends. Their findings, published earlier this month, were mixed.

“These results suggest that the proposed methods may be an alternative to the discontinued GFT and that further improvements in the quality of subregional nowcasts may require increased access to more finely resolved surveillance data,” the authors wrote.

In short, the team’s method beat an autoregressive model but underperformed compared to GFT. When the method was altered to include subregional surveillance data, it fared better versus GFT. Due to the proprietary nature of Google’s product, it’s not clear whether GFT performed better due to access to a fuller set of data, or it simply had better methodology.

The study also found that states with larger populations were easier to accurately assess, likely due to the increase in available data points.

Study co-author Sasikiran Kandula, MS, of Columbia University, says acquiring accurate local data is a major hurdle.

“Starting this season, CDC is releasing data at state level, and this may improve the nowcasts, although we have not yet had a chance to assess,” Kandula tells Healthcare Analytics News™.

However, Kandula says, public health agencies are likely the best route to accurate and robust information, since private companies might lack the incentives to regularly publish such data.

“And if they do make them public, translating this data into reliable estimates of disease incidence is far from straight-forward,” Kandula says. “I doubt they are an alternative to public health surveillance systems.”

As the team from Columbia works to improve its nowcasting modeling, the researchers envision a future when subregional data can be leveraged to help healthcare organizations better plan for influenza outbreaks.

“The forecasts may be useful to hospital administrators to allocate beds, manage staffing, [and] supplies; and for local departments of health to distribute PSAs, push vaccination drives or decide on school closings,” Kandula says.

The study, titled “Subregional Nowcasts of Seasonal Influenza Using Search Trends,” was published Nov. 6 in the Journal of Medical Internet Research.