How a Learning Health System Can Unlock the Nuances of Pain and Opioid Abuse

“We need to transform our clinics into research labs. We need high-value data from every single patient visit.”

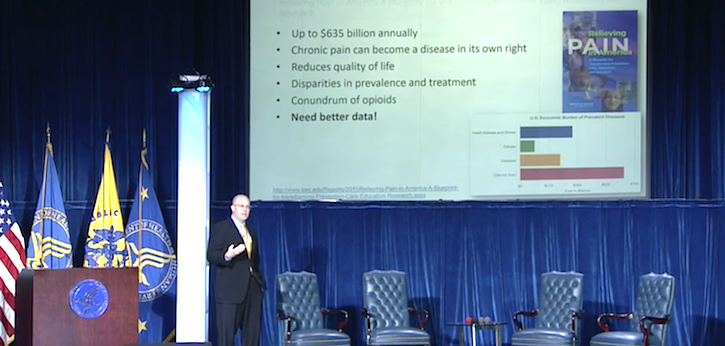

“I’m not pro-opioid or anti-opioid, I’m pro-patient,” Stanford University’s Sean Mackey, MD, PhD, said early in his speech at a Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) symposium yesterday. The meeting, held in conjunction with a competitive “code-a-thon,” was focused on the role data can play in the fight against the opioid crisis.

Mackey is Chief of the Division of Pain Medicine at Stanford, and he also co-chaired the HHS’s National Pain Strategy. He understands that opioid abuse is a major problem in the US, but also that the drugs are often helpful in treating another public health scourge: chronic pain, which 1 in 3 Americans suffer from.

To address the problem, Mackey said, healthcare needs to look at all of the aspects of pain management and opioid use to understand how patients can be given effective relief without being put at risk for lifelong addiction. A learning health system that incorporates science, informatics, incentives, and culture can be used to improve protocols over time. But to build one, clinicians and researchers need data.

“At the core of all of this, we called out for better quality data, and we need to do better and make that data actionable,” he said.

Stanford’s Collaborative Health Outcomes Information Registry (CHOIR) system is a response to that need. The system's simple interface allows participating clinicians to input qualitative data from each of their patient visits to understand how those suffering from chronic pain are responding to treatment.

“We need to transform our clinics into research labs,” he said. “We need high-value data from every single patient visit.”

Population health databases can be valuable, Mackey said, but they are often missing key phenotype information when it comes to chronic pain conditions. Electronic medical records (EMR) platforms haven’t been ideal for trying to build these data sets. They are difficult to integrate into point-of-care workflow, he said, and some vendors move “glacially” when asked for aggregate data reports.

So far, CHOIR has compiled information about more than 30,000 individual patients across over 100,000 patient visits. The system is open-source and flexible, and Mackey expressed confidence in its ability to improve learning health systems, which are meant to be “agile and nimble.”

A system like CHOIR can be used to detect patient factors that have gone previously unseen. Patient-reported fatigue, for example, is associated with physical function in chronic pain sufferers. Understanding demographically who is at risk for fatigue can also paint a picture of how it dictates opioid prescribing practices.

There are other trends that a learning health system can detect. CHOIR data was used to find out that males suffering chronic pain were more likely to be put on an opioid based on the intensity of their pain, while females were more likely to receive a prescription if they were catastrophizing (displaying a psychological fixation on the pain).

Chronic pain and opioid abuse, according to Mackey, are dual crises that are intricately connected. A learning health system that can begin drilling into those intricacies can both change the culture of medicine and how patients are treated, he said.