How COVID-19 has changed the game for medical schools

Medical colleges weathered gut-wrenching financial pressures and had to revamp their operations. The leaders of two institutions outlined the lessons they’ve learned and the challenges they're facing.

The COVID-19 pandemic delivered unprecedented challenges to America’s medical schools and the leaders of those institutions had to radically reconsider virtually every aspect of what they do.

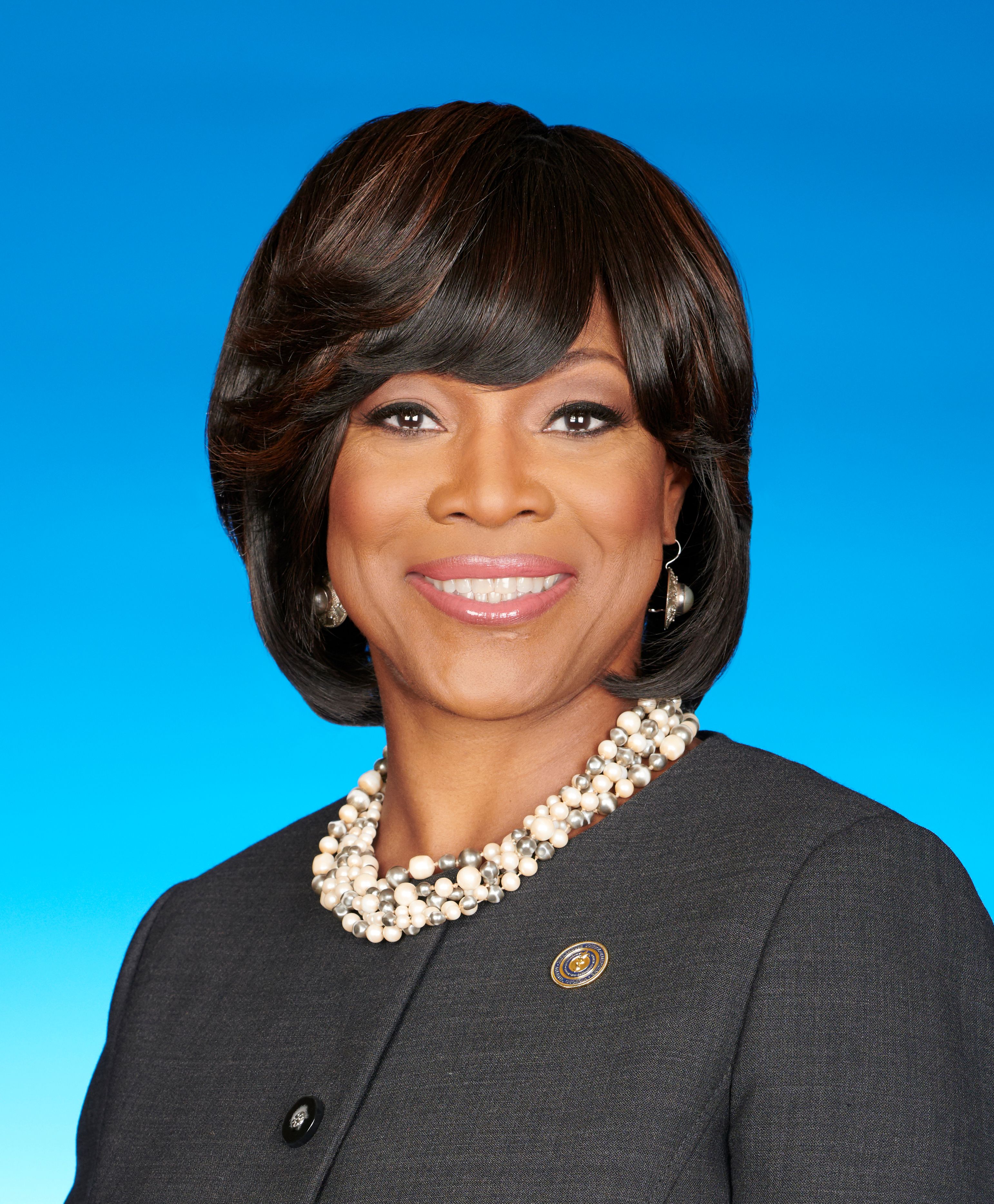

Valerie Montgomery Rice

At the Association of American Medical Colleges conference this month, the leaders of two schools discussed the financial challenges of the pandemic. They outlined the obstacles they faced and the opportunities they see in the future.

Valerie Montgomery Rice, president and CEO of the Morehouse School of Medicine, summed it up this way as she looks ahead to 2022.

“We are trying to act on the lessons learned and we are still in learning mode,” Rice said.

Leaders of Morehouse and the University of Colorado School of Medicine shared what they have learned and what they are still trying to figure out.

Financial challenges

The pandemic affected all aspects of the finances of medical schools. Elective surgeries were put on hold, cutting off a significant source of revenue.

Students and researchers were sent home during the lockdown. Some students had their own financial hardships.

John Reilly

John Reilly, vice chancellor for health affairs and dean of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, described the financial woes bluntly.

“At the beginning of this we were really, really scared this was going to jeopardize the future of this institution,” he said. “And while we had a substantial financial impact, it was not as severe or sustained as we had initially feared.”

Morehouse and the University of Colorado medical school both managed to avoid layoffs, although they employed some temporary reductions in pay or the use of furloughs in some cases.

Both medical schools were buoyed by federal COVID-19 relief aid. However, Reilly said the school had to consider how to distribute the money carefully.

“The challenge has been the moving federal guidance for what you can actually use the money for,” Reilly said.

While he stressed he was grateful for the aid, Reilly said administrators didn’t want to start distributing it to departments and then grab it back.

Investing in people

Both Reilly and Rice said they prioritized in putting some of the federal aid toward the staff who worked incredibly hard during the pandemic

“We wanted to make sure we were great stewards of the dollars and we’ve tried to make sure we invest it first in the human capital,” Rice said.

“Reinvesting in our people has been very, very critical,” she added.

Leaders from the schools also talked about planning and budgeting for uncertain financial challenges.

Going forward, Reilly discussed examining “what kind of compensation models are appropriate across our departments and which provide the most resilience for variable business conditions.”

Telehealth

The use of telemedicine has exploded during the pandemic and Reilly and Rice said they expect it to continue.

In Feburary 2020, Reilly said the Colorado system had 300 telehealth visits. By the second week of April, the system was doing 4,500 telehealth visits per day.

“That is one of the lessons learned from COVID. That has assumed a large part of our practice going forward,” he said.

Telehealth usage has dropped a bit since the peak of the pandemic, but it’s still far above what it had been, he said.

“Telehealth is still 15-20% of ambulatory volume, which is probably a 100-fold more than it was prior to the COVID pandemic,” Reilly said.

Working differently

Both medical schools have employees and staff working in person and remotely. With the increasing shift to working remotely, Reilly said he’s been able to hire employees without having them relocate to Denver.

Employees have shown they can work well remotely, Rice said, but it does pose some challenges in terms of equity. Morehouse strives to accommodate those who need to work at home, including parents with children in school. But she noted, many in the medical field obviously can’t work remotely.

“Surgeons don’t get to operate from home, right? I know people who work in clinics, in the clinical environment, don’t get to work from home,” Rice said. The challenge is creating equity for those workers, she said.

Meetings involving remote employees and those in the facilities also can be tricky, Reilly said.

“Hybrid meetings work well for dissemination of information,” he said. “They don’t work as well for a lot of interactive discussion.”

The spontaneous collaboration that happens when employees see each throughout the day can’t be replicated as easily with those working remotely.

“The world of Zoom means you have to schedule everything,” Reilly said. “That cuts down on that informal chat which turns out to be a valuable corridor for communication in the organization.”

Health equity

The leaders of both medical schools said the pandemic vividly illustrated how health outcomes vary widely based on socioeconomic factors.

Rice, who leads one of the nation’s four historically Black medical schools, said she has been surprised that so many are now understanding the challenges of health equity. Between the pandemic and the social justice debates that emerged following the killing of George Floyd, she said many are vividly understanding health inequity for the first time.

“They were able to finally sort of connect the dots about the social and economic impact and how that can lead to health inequities,” Rice said.

At the height of the pandemic, Reilly said more than 40% of the Colorado system’s patients were Hispanic patients.

Walking through intensive care units filled with Hispanic and Black patients “was a signal that nobody could ignore,” Reilly said.

Morehouse has teamed with CommonSpirit Health in a $100 million partnership to train more Black doctors and address healthcare disparities.

The University of Colorado medical school is aiming to add more diversity to its faculty ranks, Reilly said.

“We are pretty intentionally, but not moving as fast as I’d like, to try and diversify our workforce so it more accurately represents the population we serve,” he said.

Telehealth faces a looming deadline in Washington | Healthy Bottom Line podcast

February 12th 2025Once again, the clock is ticking on waivers for telemedicine and hospital-at-home programs. Kyle Zebley of the American Telemedicine Association talks about the push on Congress and the White House.