Healthcare cyberattacks have affected more than 100 million people in 2023

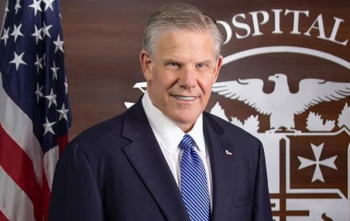

The number of people affected by breaches appears to be an all-time high. John Riggi, cybersecurity advisor for the American Hospital Association, talks about trends in attacks, threats to patients and the AI arms race.

It appears that 2023 will be the worst year ever for cyberattacks aimed at healthcare organizations.

The number of attacks isn’t necessarily higher than the past few years. But the attacks have been more damaging and affected more people, says John Riggi, national advisor for cybersecurity for the American Hospital Association.

“I think this year we are going to break all records in terms of the number of individuals impacted,” Riggi tells Chief Healthcare Executive®.

About 106 million individuals have been affected by cyberattacks involving healthcare organizations, Riggi says, pointing to federal data on breaches of health data. For perspective, about 44 million people were affected by breaches of health information in 2022, so the number of individuals affected this year has more than doubled.

Put another way, nearly 1 in 3 Americans have been affected by a health data breach this year.

Riggi says the number of victims this year is likely to grow, since some attacks may not have been reported yet to the government. The U.S. Department of Health & Human Services requires organizations to disclose any breach of health data involving at least 500 individuals.

With around 475 attacks reported this year, Riggi estimates there will be about 500 hacks reported in 2023. The average breach is affecting more than 200,000 individuals, Riggi says.

“The bad guys have figured out it's not the number of attacks. It's where you attack,” he says.

“So they're gaining access to data databases that have large volumes of data.”

In a conversation with Chief Healthcare Executive, Riggi discussed trends in recent attacks, the threats to health organizations and patient care, what the government is doing, and the AI “arms race” in cybersecurity. (Cybersecurity experts talk about emerging threats in this video. The story continues below.)

‘No organization is immune’

Some of America’s largest healthcare organizations have suffered ransomware attacks this year.

Just last month,

Health systems and hospitals have been victimized by attacks on third-party services or breaches targeting their vendors and contractors, Riggi says.

Many healthcare organizations were affected by a breach involving MOVEIt, a well-known file transfer tool, he notes. A Russian ransomware group known as Clop was responsible for the attack. The

While not referring to any specific attacks, Riggi notes that the breaches this year show that all health systems and hospitals are vulnerable, even large organizations.

“It just goes to show one that no organization is immune, that no matter how much money you throw at this problem, we can't defend our way out of this issue,” Riggi says. “There will always be some vulnerability present in any system, including government organizations, which have been victimized this year as well.”

Hospitals are encountering more ransomware attacks, Riggi says.

Ransomware groups are infiltrating software and encrypting networks and seeking payments from hospitals to restore access to networks. Attackers are also stealing patient records as well.

“They are simultaneously exfiltrating data and holding that for ransom as well, as we commonly referred to it as the double-layered extortion,” Riggi says.

Increasingly, some attackers are simply going after the health data itself and holding that up for ransom. “They are just contacting the victim and saying, ‘We have your data. Pay us not to publish it on the internet and/or sell it on the dark web,’” Riggi says.

Cyberattackers typically aren’t succeeding with “zero day” breaches, or finding new, undiscovered vulnerabilities, Riggi says. However, ransomware gangs are swiftly finding existing weaknesses in software and exploiting them before they can be repaired, Riggi says.

“Often they look at the known published vulnerabilities, and they hack before we can patch,” Riggi says.

“So a bad guy, if there's a known published vulnerability, they can develop malware pretty quickly, hours or days to exploit that,” Riggi says.

Conversely, it may take a large health system weeks to address all the vulnerabilities in its software. “And often again, we're dependent on the third party provider, the developer of that technology, to provide us with the patch,” he says.

‘Threat to life’

Healthcare organizations and the federal government are paying greater attention to the risks of cyberattacks to patient safety. Cyberattacks can prevent hospitals from using electronic health records, and in some cases,

“When they attack a hospital, they are shutting down life critical systems,” Riggi says. “When they encrypt our networks and we have to shut down our network, and our internet connection is lost, that means life critical medical technology is no longer available, which causes an immediate delay and disruption to healthcare, causing the most immediate risk to patient safety and ultimately a threat to life.”

“What we see is an immediate diversion of ambulances, which may be carrying stroke, heart attack and trauma patients. And if some of the hospitals which had been shut down by these despicable ransomware attackers, the next nearest hospital may not be within close proximity, causing a significant delay in urgent treatment,” he adds.

In addition to the risks for patients coming to the hospital, a cyberattack threatens the safety of those who have already been admitted, he notes.

“We can't access their electronic medical record. We can't determine quickly what the drug allergies are,” Riggi says. “We can't determine the full history of treatment on this patient.”

Cyberattacks can also delay treatments for cancer patients. “That's not a simple thing to to easily ship off all your cancer patients to some other cancer center,” Riggi says.

Riggi says he’s encouraged that federal authorities have said they are treating cyberattacks aimed at hospitals and healthcare organizations as “threat to life” crimes. FBI Director Christopher Wray spoke to CEOs at the American Hospital Association conference in the spring and reiterated that the justice department will treat ransomware attacks as crimes threatening lives.

“Convincing the government is not the issue,” Riggi says. “It's convincing the bad guys that if they conduct an attack against the hospital, make no mistake, this is not going to be treated by the government as a white-collar crime, as a data theft crime. It should end up being a bright red line that if you attack a hospital, or any critical infrastructure that puts lives at risk, the government's coming after you.”

‘Do more on offense’

Hospitals and health systems need to make cybersecurity a high priority, and leaders generally understand the risks, Riggi says.

He says he talks to thousands of hospital executives each year, and leaders regularly tell him that cyberattacks are the one threat that keeps them awake at night. Some leaders are suggesting that they view cyberattacks as more daunting than the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They had their technology at hand to deal with that,” Riggi says. “And they weren't dealing with the human adversary. And so the CEOs are getting the message. They're ranking it as their number one, or number two, enterprise risk issue.”

While hospitals are making strides, Riggi says the government needs to be more aggressive in going after ransomware groups, including those based overseas and enjoying the support of foreign governments.

“I say to the government publicly and privately, we need to do more on offense,” Riggi says.

“It's going to take a whole-of-government approach, military and intelligence operations, combined with law enforcement interdiction of their finances,” he adds. “The government has to impose significant risk and consequences on these bad guys. It's a team sport. We've got to do what we need to do on defense, but offense is half the game.”

AI arms race

Artificial intelligence is widely projected to change healthcare, and cybersecurity analysts say AI tools could be invaluable in protecting health systems from ransomware attacks.

Conversely, analysts note that

“AI tools on the positive side can certainly help scan networks quickly, identify vulnerabilities, perhaps accelerate our ability to do that and to perhaps accelerate our ability to apply patches as well,” Riggi said.

“On the bad side of that equation …. bad guys are using AI right now to write very convincing phishing emails, write malware and code which can quickly scan our networks to identify vulnerabilities and quickly develop malware exploits based on those identified vulnerabilities.”

While he acknowledges it is too early to say definitively, Riggi wonders if AI-powered cyberattacks are a factor in the increased number of people being affected by health data breaches this year. But he says there’s no doubt that attackers are using AI.

“We are in the midst of an AI-fueled cyber arms race right now,” Riggi says. “And it's really accelerated dramatically.”