How Will New FDA Guidelines Affect Digital Health?

Paul Cerrato, M.A., and John Halamka, M.D., M.S., analyze the future of software as a medical device.

Software as a medical device (SaMD) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 510(k) clearance might not be the most familiar terms to all health system leaders, physicians and nurses who use computers, but if they hope to take advantage of the latest artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled programs, they will need to keep up. The most recent FDA proposed regulatory framework on SaMD is likely to transform patient care in the next few years. Understanding how the guidelines fit into the picture will enable clinicians and their organizations to take full advantage of the machine learning-based diagnostic and treatment algorithms now being introduced.

Deciphering the Terminology

To make sense of SaMD, it helps to understand the FDA’s expanded definition of a medical device. In the not-too-distant past, a medical device was a physical object — an EKG machine or a blood pressure cuff, for example. But the term now encompasses software used to assist in the diagnosis, treatment, mitigation or prevention of disease. As we explained in The Transformative Power of Mobile Medicine, the FDA believes that most mobile apps intended to diagnose or treat disease are “medical devices under federal statute.” On the other hand, apps or other types of software that are either designed to provide wellness services or that receive, store, transmit and offer more general health information are not considered medical devices. Software that the agency says falls into the SaMD category includes:

- Mobile apps that transform a mobile platform into a regulated medical device and therefore are mobile medical apps: These mobile apps use a mobile platform’s built-in features such as light, vibrations, camera or other similar sources to perform medical device functions (e.g., mobile medical apps that are used by a licensed practitioner to diagnose or treat a disease).

- Mobile apps that connect to an existing device type for purposes of controlling its operation, function or energy source and therefore are mobile medical apps: These mobile apps are those that control the operation or function (e.g., change settings) of an implantable or body worn medical device.

- Mobile apps that are used in active patient monitoring or analyzing patient-specific medical device data from a connected device and therefore are mobile medical apps.

Although the FDA’s position on SaMD was designed to protect the public from unscrupulous vendors who create ineffective or unsafe digital tools, since publishing these regulations, the agency has come to realize that they might be too restrictive in some situations and could actually damper healthcare innovation. That’s especially the case when it comes to machine learning-based software. A closer look at the FDA clearance/approval process helps explain why this problem has arisen.

Medical device applications are handled with three processes:

- Premarket clearance, also called 510(k)

- Premarket approval

- De Novo classification

A 510(k) submission seeks to gain clearance of a device that is at least as safe and effective as a legally marketed device that’s already available to the public. Premarket approval, on the other hand, is a more stringent review process required of Class III medical devices, which support or sustain human life or “which present a potential, unreasonable risk of illness or injury.” De Novo classification applies to novel medical devices “for which general controls alone, or general and special controls, provide reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness for the intended use, but for which there is no legally marketed predicate device.” Unfortunately, AI and machine-learning algorithms do not easily fit into any of these 3 classifications, which has forced FDA to develop a new approach, which it has published as Proposed Regulatory Framework for Modifications to Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Based Software as a Medical Device (SaMD).

Why Do We Need New SaMD Rules?

The need for new regulations can be summed up in two words: adaptive technology. The current regulations were designed to handle “locked” technology, such as software whose functioning does not change. Because many machine-learning systems are self-learning, by definition the software does change, adapting to new input from training and test data sets. In FDA parlance, these software systems “have the potential to adapt and optimize device performance in real-time to continuously improve healthcare for patients.”

To cope with this new situation, the agency is proposing what it calls a “predetermined change control plan” for device developers who are seeking premarket clearance. Submitters would have to provide FDA with a plan that spells out the types of anticipated modifications they see coming down the road, as well as the methodology they plan to use to implement these changes in a controlled manner. The ultimate goal of such a plan is to manage patients’ risk from the software. Vendors who agree to this proposed arrangement would be expected to commit to transparent, real-world performance monitoring of their AI and ML software. They would also be willing to provide periodic updates to the agency. According to FDA, this new approach to SaMD would allow the regulator to embrace the iterative improvement power of AI- and machine learning-based software as a medical device, while assuring patient safety.

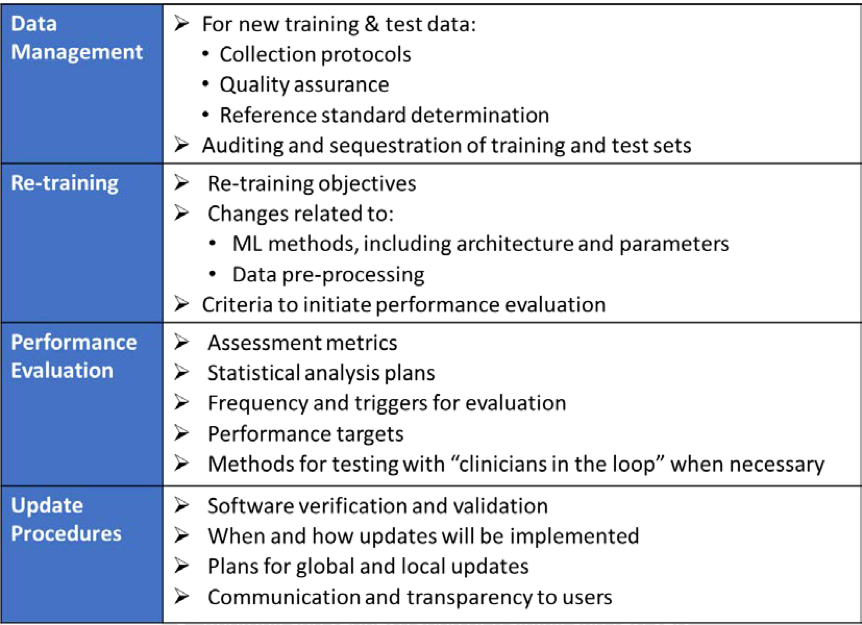

To understand how the proposed regulatory framework world work in the real world, one first needs to grasp two rather obscure terms that the agency has introduced: SaMD pre-specifications (SPS) and algorithm change protocol (ACP). SPS refers to the types of changes that a vendor plans to implement in its software. In other words, the company has to spell out what its algorithm is supposed to become as it learns from its new inputs, namely the new training and testing data that it encounters. ACP describes the method the vendor plans to use to make sure the revised algorithm performs as expected. The guidelines explain: “The ACP is a step-by-step delineation of the data and procedures to be followed so that the modification achieves its goals and the device remains safe and effective after the modification.” The agency envisions four components to this change protocol, as outlined in the Figure.

Putting the FDA Framework to the Test

These proposals might sound rather vague without a real-world example of how they might apply to an actual AI/ML system. Imagine a mobile app that allows a smartphone to take a photo of a skin lesion so that a physician can make a clinical judgement about whether it’s a normal mole or skin cancer. Since the app drives clinical management of a serious healthcare problem, it’s considered a medical device that falls within the FDA’s jurisdiction. If a vendor decides it wants to modify the app, it first has to explain what changes it plans to make — the SPS portion of the review process. The FDA framework document gives possible modifications. For instance, the algorithm may be exposed to a new data set with images of skin lesions with the goal of improving its sensitivity and specificity. A more sensitive algorithm is more likely to detect true positive findings, such as how the number of photos identified as skin cancer that really are skin cancer would increase as a result of the new training. The software would be more specific if it succeeded in identifying more true negatives, such as how the number of photos labeled as not skin cancer that really aren’t skin cancer would increase.

The change protocol or ACP for this dermatologic app would involve the manufacturer submitting to FDA its method for making these improvements. The developer would have to explain how it generated the data set, discuss reference standard labeling and provide a comparative analysis and performance requirements, including sensitivity and specificity. If the vendor could collect the needed data and demonstrate its improved sensitivity and specificity, and it updated its labeling and communicated the improvements to its audience, “the modified algorithm that ‘learned’ on real-world data can be marketed without additional FDA review.”

On the other hand, if this same hypothetical app manufacturer wanted to sell this mobile app to patients to use on their smartphones, it would face a different regulatory scenario. The vendor would direct patients to follow up with a dermatologist after receiving a preliminary analysis of a malignancy. And most important, because the app now introduces new risks that were not addressed in the current SPS or ACP, the vendor might have to obtain a new premarket submission or application and submit an updated SPS and ACP.

Industry Feedback on SaMD Regulations

The agency hopes that by outlining these two scenarios — one in which the company requires additional FDA clearance or approval and one in which it does not — it will convince developers that it’s becoming more flexible and is fostering innovation. The proposed framework was released in April 2019 for public comments; the comment period closed on June 3. Some commenters urged the agency to include software in medical devices, not just software that acts as a medical device. Others asked for better definitions of machine learning and more clarity on terms like “locked down” and “continuous learning” algorithms. Many wanted the agency to provide more examples of how changes in AI/ML software might trigger an expectation of premarket review. Allison Fulton, a lawyer with the Life Sciences and FDA team at SheppardMullin, believes that, “While the industry largely encourages FDA to react quickly to evolving technology so as not to stifle innovation, the agency will have to take time to more clearly define foundational terms in this complex area and clarify its expectations for software developers and medical device companies.”

It’s impossible to predict how the FDA will respond to all these comments. And the departure of Scott Gottlieb, M.D., as commissioner adds to this uncertainty. But it seems the policies and philosophy put in place by Gottlieb may well continue to steer the ship. According to Aaron Josephson, who spent a decade at FDA, “… I do not expect the tone and agenda to change with whoever is named acting commissioner or is ultimately confirmed to replace Dr. Gottlieb. [Ned Sharpless, M.D., is now acting Commissioner.] During my time at the FDA, I worked with the team of staff who helped Dr. Robert Califf transition into his role as commissioner. Similarly, I was on the team of staff who aided the Trump administration's early FDA appointees (before Dr. Gottlieb was confirmed) in understanding the agency and prepared Dr. Gottlieb for his return to the agency. During both transition periods, the agency's core business — reviewing applications for new medical products and protecting marketed medical products and food — continued without issue thanks to the efforts of the FDA’s talented career staff and the statutory mandates FDA is required to satisfy.”

One reason to be optimistic about the FDA’s position on SaMD is the fact that much of SaMD’s future has already been decided by Congress with the passage of the 21st Century Cures Act, passed in December 2017 to encourage innovation. Section 3060, which deals specifically with regulation of medical devices, “expressly excluded from the definition of medical device five distinct categories of software or digital health products,” according to one expert. After the Cures Act was passed, the FDA released several guidelines to help developers and clinicians understand its implications, including a set of guidelines on SaMD.

Attorneys with Arnold & Porter explain that the guidelines established a three-step clinical evaluation process that “emphasizes that the level of evaluation and independent review should be commensurate with the risk posed and encourages manufacturers to use continuous monitoring to understand and modify software based on real-world performance.” The key word here is risk. While entrepreneurs planning to invest in SaMD would be wise to seek the advice of lawyers with expertise in the intricacies of FDA regulations, the agency is making it clear that it wants to give developers more room for innovation, especially if their products pose little risk of harming patients.

About the Authors

Paul Cerrato has more than 30 years of experience working in healthcare as a clinician, educator, and medical editor. He has written extensively on clinical medicine, electronic health records, protected health information security, practice management, and clinical decision support. He has served as editor of Information Week Healthcare, executive editor of Contemporary OB/GYN, senior editor of RN Magazine, and contributing writer/editor for the Yale University School of Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, Information Week, Medscape, Healthcare Finance News, IMedicalapps.com, and Medpage Today. HIMSS has listed Mr. Cerrato as one of the most influential columnists in healthcare IT.John D. Halamka, M.D., leads innovation for Beth Israel Lahey Health. Previously, he served for over 20 years as the chief information officer (CIO) at the Beth Israel Deaconess Healthcare System. He is chairman of the New England Healthcare Exchange Network (NEHEN) and a practicing emergency physician. He is also the International Healthcare Innovation professor at Harvard Medical School. As a Harvard professor, he has served the George W. Bush administration, the Obama administration and national governments throughout the world, planning their healthcare IT strategies. In his role at BIDMC, Dr. Halamka was responsible for all clinical, financial, administrative and academic information technology, serving 3,000 doctors, 12,000 employees, and 1 million patients.

Get the best insights in digital health directly to your inbox.

Related

Tackling the Misdiagnosis Epidemic with Human and Artificial Intelligence

Replacing Old-School Algorithms with New-School AI in Medicine

Podcast: Adoption of Healthcare Tech in the Age of COVID-19 with Dr Kaveh Safavi

June 22nd 2021Kaveh Safavi, MD, JD, global health lead of Accenture Health, discusses how the pandemic influenced the speed at which healthcare organizations adopted new technologies and how this adoption is impacting patient care.