Hospitals must train staff to help LGBTQ+ patients

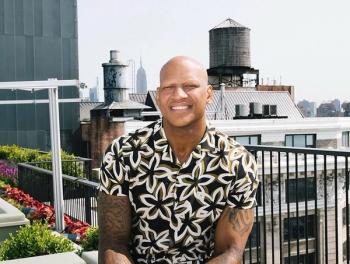

Health systems need to work with employees on showing sensitivity, and that should be a priority throughout the organization, says Dr. Dustin Nowaskie of OutCare Health.

When it comes to treating LGBTQ+ patients and making them feel welcome, clinicians have some work to do.

A little more than half (54%) of LGBTQ+ individuals say they trust primary care providers, compared to 70% of heterosexual respondents, according to a recent

Dr. Dustin Nowaskie is the president and founder of OutCare Health, a nonprofit organization helping LGBTQ+ patients find clinicians and advocating for health equity.

But Nowaskie, a queer, nonbinary psychiatrist, says it’s time for more providers to be offering affirming care. Nowaskie says it’s critical for hospitals, health systems and medical practices to provide training in caring for LGBTQ+ patients.

“Most people in the world are not malignant,” Nowaskie says. “They're just uneducated. They're unaware. And so starting with that education is very foundational, but the biggest barrier is implementing all that knowledge that you've learned into practice.”

Look at the entire staff

OutCare Health provides training to providers on working with LGBTQ+ patients and making them feel safe and accepted.

“We work with many industries, healthcare, non healthcare, hospitals, clinics,” Nowaskie says.

Organizations need to think about their entire ecosystem, and when OutCare Health works with a hospital or clinic, they ask to conduct training of all employees. Some health systems and hospitals are looking to educate their clinicians working with patients, but they must also train everyone throughout the organizations, including receptionists and security guards, Nowaskie says.

“Providers went to graduate education, they want to help people,” Nowaskie says. “They have a foundational understanding that there are marginalized people that have disparities.”

But Nowaskie continues, “Often, what we find is some of the biggest opportunities for improvement within systems, typically involve everyone else … The staff members, the people who are greeters, the people at the front desk, the people that are making calls, may often have never received any type of equity training, especially LGBTQ+ education.”

Some sexual and gender minority patients report gaps in cancer care, including a lack of cultural competence and training among staff and providers, according to a

Health systems should offer staff training on a regular basis, rather than viewing it as once-and-done.

“I would say, for providers, especially, engaging in longitudinal, lifelong learning for LGBTQ+ people is paramount,” Nowaskie says.

As providers get more training in working with LGBTQ+ patients, Nowaskie says they should also be advocates for those patients and push for change in their organizations.

If health systems aren’t thinking comprehensively about training, then LGBTQ+ patients may feel unwelcome and decide against coming back, even if they had a good experience with doctors and nurses.

“The last thing that anyone wants is to see a great provider, but then not feel so affirmed in the system,” Nowaskie says. “I've seen a lot of patients where they say, ‘I had a great provider, but I was discriminated against. I felt uncomfortable going into the clinic because there was no iconography, there were no affirming symbols, or, you know, I didn't feel welcomed.’ And so it has to be the entire system approach.”

Some avoid clinicians

Nowaskie says there are lasting consequences when hospitals and other providers don’t offer a welcoming experience to LGBTQ+ patients.

Some don’t get regular checkups and avoid doctors altogether, or they wait until they have more advanced illness and treatment becomes more complicated.

“As a psychiatrist, I've actually cared for a handful of patients where I'm the first provider they've seen in over 10, 15, even sometimes 20 years, because of something that happened in a discriminatory way from a healthcare provider or someone within healthcare, like a healthcare staff member, someone making a phone call,” Nowaskie says. “And the stigma that occurs within healthcare can be so profound, it can lead people to delay care or to forego their entire medical journey, because of something that happened that long ago.”

Transgender and gender diverse people are less likely to engage in regular cancer

cancer screening programs and have a higher incidence of HIV- and HPV-associated cancers, according to a 2023

Nowaskie would like to see more focus on caring for LGBTQ+ patient in medical schools and nursing schools. While some institutions are doing more, Nowaskie says some schools are only offering a couple of hours of education per year, compared to just an hour several years ago.

“It is an improvement, but it is nowhere near the amount that they need to really talk about this complexity and intersectionality of healthcare and identity,” Nowaskie says.

Nowaskie says medical students, and learners in general, would benefit most from 35 to 50 hours of training in caring for LGBTQ+ patients.

In addition, Nowaskie says there should be more training for other healthcare providers.

“For many specialties, like nursing, social work, dentistry, occupational therapy, physical therapy, they are devoting even less amounts of education and training, and they need just as much as any provider out there,” Nowaskie says. “And so it's unfortunate there are very glaring gaps in LGBTQ+ education and training nationwide.”